First, a few words

The past is a powerful presence of the present.

I am reliably told by my parents that I was born on Sunday 4 December 1955, in the location of Jabavu in Soweto. I am the second child of Mohamed Sethunya Makgari and Joyce Maqenehelo Makgari, nee’ Mosia. We originally belonged to the Bakoena clan when we adopted the Makhari surname. Later, because of phonetical changes, this became Makgari. Their first child is a girl, Masethunya.

In the communities I was born into, a belief lingered like a shadow: when a Black child was born with a deformity, it was said that the forebears were displeased, or that witchcraft had taken its toll. I entered the world already wrapped in stories I did not choose.

I was often labelled a cripple, but my parents never allowed that word to become my identity. They encouraged me to reach for the stars, reminding me that I was capable of far more than I was ever told. Their belief lit a flame in me—one that pushed me to question limitations, challenge expectations, and confront even the systems that sought to define my worth.

At age seven it was necessary or compulsory for any child to attend public school and I joined the lot. But the government had foolishly decided to remove physically disabled learners from mainstream education. Black nurses were tasked to visit schools and rake in disabled learners, take their names down and later visit their homes to let parents know of this preposterous intervention. Regardless, of what was happening, my mother always found a way to drum into my mind the invincible spirit of conquering the future at that tender age.

At school I was the child that hoppled everywhere with my head up, shoulders very high. I dragged my paralyzed led with determination, purpose, and ambition to achieve and to shame critics but to also bring untold happiness to my parents. This book is about my life story, and I dedicate it to my late mother. I am truly indebted to my children for having write this book. They have been saying that I’m too vocal on many issues, but I don’t have a book to show for this. This became an inspiration for me to produce this book.

I grew up with two girls with attributes of a real boy. I played with other boys my age as normally as my character and physical condition allowed. I joined street football games and was almost always the goalkeeper. I never saw myself as different. My mother made sure of that. Because of her, I walked into every space — even the ones designed to exclude me — believing I had a place there.

Excellence in Mathematics & Science

Before the book, before the labels, there was the classroom.

I passed matric with exemption. Only eight learners passed mathematics that year, and I was among them. My name, like those of all matriculants, was splashed across national newspapers. You can imagine my mother’s happiness. In my community, I was soon given a new name: Doctor Makgari.

That academic foundation carried me forward. In Heilbron, in the Free State, I became known as one of the notable Mathematics and Science teachers. Teaching was not simply a profession, but a continuation of the same belief that had sustained me from childhood: that ability must be nurtured, not dismissed, and that potential often hides where society least expects it.

This recognition was never about titles. It was about proof. Proof that excellence could emerge despite doubt, despite barriers, and despite the limitation’s others tried to impose.

By the time I reached Grade 12, I was consistently achieving straight A’s. My fluency in English had revealed itself much earlier, already apparent when I was in Standard 5. At school, academic success became one of the few spaces where my ability could not be ignored.

In the process, I became what some called a bullet. I was labelled brilliant, and at times even a genius. These labels followed me easily, attached to results rather than understanding, and they were accepted without question.

But this was a misunderstanding. Intelligence was confused with opportunity, and academic performance was mistaken for innate brilliance. This mislabelling continues even today, quietly shaping how people think about IQ and potential, and misleading many across different spheres of life.

Setbacks, Work, and the Will to Continue

I began my first year at the University of the North, Turfloop, pursuing a BSc. By the end of that year, I had failed. The disappointment cut deeply, and my spirit dimmed under the weight of expectation and self-doubt

In 1978, I took my first job with Roberts Construction as a Costing Clerk. My aim was simple: to earn enough money to return to university. During this time, I worked closely with the foreman, Mr Olivier, who admired my work ethic and documentation skills. His confidence in me led to a transfer to a new site in Potchefstroom, where opportunity briefly felt within reach. That relationship ended abruptly when he learned of my intention to return to school. What followed was unexpected and painful. False reports were sent to Head Office in an attempt to prevent my deregistration, turning trust into hostility almost overnight.

In 1979, I returned to university. During recess, I applied for a position at Anglo American. I passed the psychometric tests and later received a telegram offering me the job. Yet before I could begin, I was judged. My disability became the deciding factor. I was denied the opportunity, dismissed as cursed before my work could speak. Still, the story did not end there. In 1980, after being turned away by Anglo American, I secured a position at Con Roux (Pty) Ltd. Despite the obstacles, I interviewed, passed, and was appointed. It was not an easy victory, but it was one I earned.

Matters of the Heart

I experienced love for the first time and felt the simple joy of being accepted as a “normal” person. That happiness was short-lived when I discovered she was carrying another man’s child. The heartbreak was deep, but it did not define me, nor did it stop me from opening my heart again.

Over time, I found myself entangled with three women, each unique and each offering the possibility of a future. Choosing between them was a challenge I could not face alone. With guidance, I made a decision that went against my initial feelings, selecting the one I felt least drawn to.

The expectation was high, and gossip flew through the township: some said no girl in her right mind would marry a disabled man, suggesting that my bride-to-be must be disabled too. Yet, on December 4, 1983, wedding bells rang, ululations echoed in the neighborhood, and the township buzzed with news of a wedding in full swing.

She became my wife, standing by me through life’s trials until her passing. Between courtship and marriage were the negotiations of lobola, a cultural rhythm that grounded our union even as the journey tested patience, trust, and resolve.

Books & publications

2025

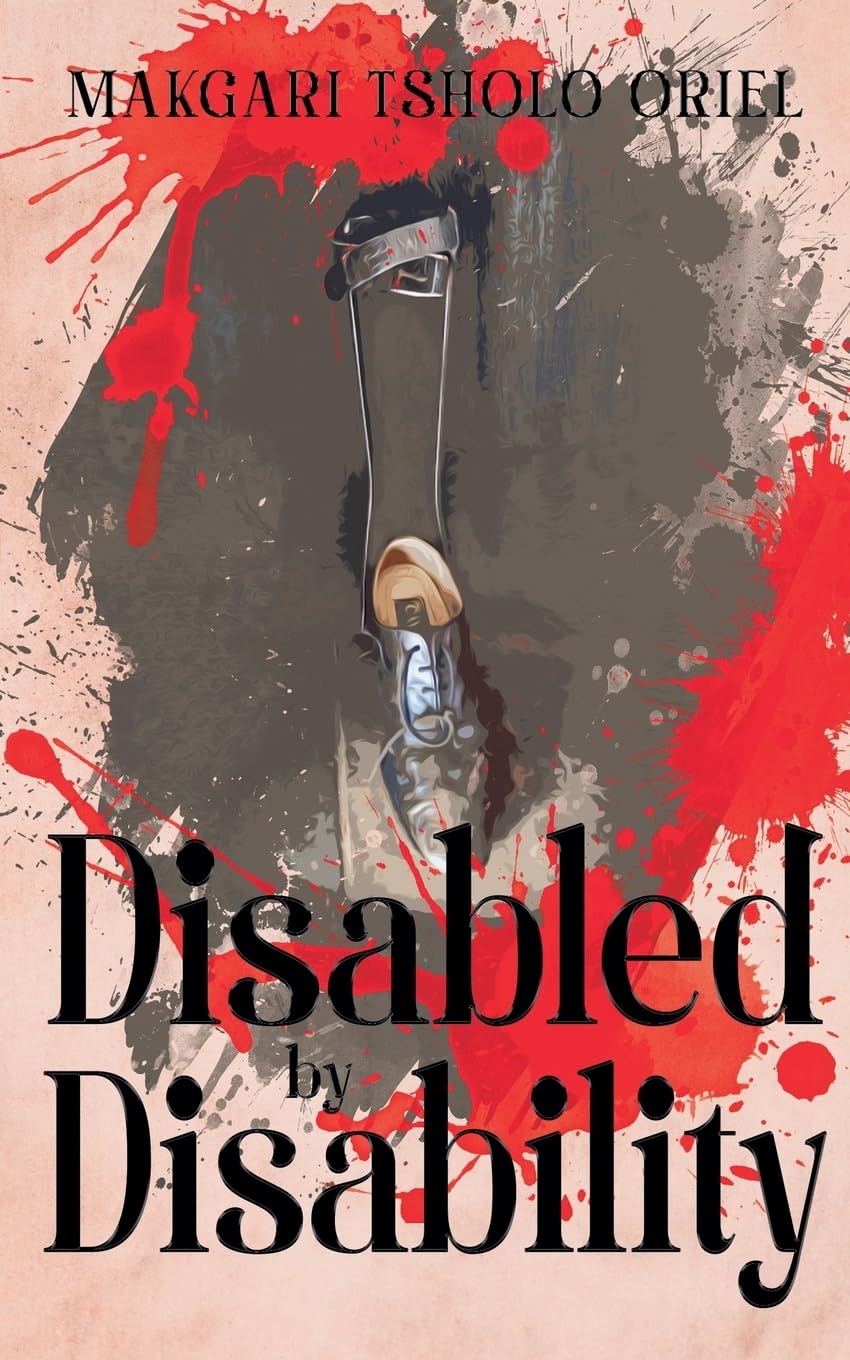

Disabled by Disability

“This book forces you to want to see the author in person.” – Prof. Caleb Mabelane

Qualifications must correlate with one’s actions otherwise they are meaningless.

Makgari Tsholo Oriel